Let Freedom Swing

Let Freedom Swing brings outstanding performances to community audiences. Offering performances, workshops, collaborations, and instrumental clinics for audiences of all ages, Let Freedom Swing explores a wide range of jazz topics through the lens of American history. Since 2013, Let Freedom Swing has reached over half a million people in over 3,500 concerts around the world.

Jump to

EDUCATION

Jazz and the Great Migration

Jazz and the Great Migration

The largest human migration in American history began in 1915. Over the next half-century, nearly six million African Americans packed their belongings, left their homes in the Jim Crow South, and set out for the big cities of the North in search of jobs and freedom. Known as the “Great Migration,” the poet Alain Locke wrote, this mass movement was “a deliberate flight not only from countryside to city, but from medieval America to modern.”

City life in the North was immeasurably enriched by the arrival of so many strangers from the South. But American culture was transformed forever because jazz was part of the newcomers’ baggage. Wherever they settled it found eager new audiences. New York’s Harlem, Chicago’s South Side, the wide-open streets of Kansas City Missouri, the Paradise Valley neighborhood in Detroit, Central Avenue in Los Angeles, and many other new jazz-rich big-city enclaves all across the country became proving grounds for America’s music.

The Harlem Renaissance

Each city was important to the music’s development, and each added its own unique flavor to the mix. Still, as Duke Ellington remembered, “Harlem in our minds had the world’s most glamorous atmosphere. We had to go there.” Ellington moved from Washington, D.C. to Harlem in 1923. Other eager young musicians flocked there, too. Harlem was then the cultural capital of black America, home to the Harlem Renaissance, a remarkable coalescing of African American artists, that included activists W.E.B. DuBois and Marcus Garvey, and the writers James Weldon Johnson, Langston Hughes, and Zora Neale Huston.

All kinds of jazz flourished in its cabarets and nightclubs and dance halls but in the 1920’s, one solo piano style seemed especially well suited to the city’s fast-paced, competitive spirit. Harlem stride or “eastern ragtime” is “orchestral piano,” one practitioner said: While the left hand “strides,” establishing a steady rhythm by alternating between bass notes at the end of the keyboard and chords around its middle, the right hand is free to play swinging, intricate melodies as if it were a horn. Two stride-masters stood out above the rest, James P. Johnson and his friendly rival, Willie “The Lion” Smith.

“Sometimes we got carving battles going that would last four or five hours,” the Lion remembered. Rent parties were their specialty—all-night dances held in crowded apartments where the price of admission helped keep the landlord at bay. “They would crowd a hundred people … into a seven-room railroad flat,” the Lion recalled, “and the walls would bulge—some of the parties spread to the halls and all over the building.” He and Johnson usually fought to a draw, Duke Ellington remembered. “It was never to the blood. With those two guys it was always a sporting event. Neither cut the other. They had too much respect for that.”

Key Figures

Duke Ellington

DUKE ELLINGTON was born in Washington, D.C. on April 29, 1899. His parents both played piano and they encouraged their son to study music at a very early age. In 1923, Duke moved to New York, where he joined the cultural revolution known as the Harlem Renaissance. Composer Will Marion Cook advised young Ellington, “First…find the logical way, and when you find it, avoid it and let your inner self break through and guide you. Don’t try to be anybody else but yourself.” It was a lesson Duke would carry throughout his career.

Thomas “Fats” Waller

THOMAS “FATS” WALLER had such a magnetic personality and was such a consummate showman, one younger musician remembered, that “you could never be sad in his presence.” Waller’s bubbling stage persona—leering and lampooning the tunes he sang and played, shouting to urge his men on—often hid the master he really was. After Duke Ellington, Waller was the most prolific and successful songwriter to emerge from the world of jazz. Songs like “Ain’t Misbehavin’,” “Honeysuckle Rose,” and “Keepin’ Out of Mischief Now” (all written with lyricist Andy Razaf) became American standards and helped make him nearly as celebrated in his lifetime as his friend Louis Armstrong. He was also the first jazz musician to record on the organ, but his most lasting impact was as a pianist. Building upon the Harlem stride he learned from his mentor, James P. Johnson, Waller developed his own irresistibly swinging style. His tireless left hand set the driving pace while his right served up delicate figures that continue to dazzle pianists. Jimmy Rowles marveled that Waller seemed able to “think in two directions.” “Fats,” said Art Tatum, “that’s where I come from.” And Mary Lou Williams urged students hoping to learn how to play jazz to “go back to Fats Waller. That’s the metronome.”

Ella Fitzgerald

“If the musicians like what I do,” ELLA FITZGERALD once said, “then I feel I’m really singing.” She was a child of the Great Migration, born in Virginia but brought north to Yonkers, New York as a little girl. Discovered at 16 after winning an amateur night contest at the Apollo Theater in Harlem, she first won fame in the late 1930s, performing novelty tunes and romantic ballads with the hard-swinging Chick Webb Orchestra. During the 1940s, she recorded with every kind of backup group and established herself as a master of scat singing, incorporating the fresh harmonies and rhythms of bebop into wordless acrobatic performances that astonished audiences and musicians alike. Her gift of swing, impressive scatting, precise diction, and extraordinary range made her as adept a soloist as any horn player. Then, in the 1950s, she recorded definitive versions of standards by America’s greatest songwriters, from Cole Porter to Duke Ellington. Through it all, she never lost the girlish joy evident on her earliest records, never seemed to sing out of tune, and never failed to swing. Musicians were awed by her musicianship. For her, “music is everything,” her sometime accompanist Jimmy Rowles said. “When she walks down the street, she trails notes.”

“Jazz calls us to engage with our national indentity. It gives expression to the beauty of democracy and of personal freedom and of choosing to embrace the humanity of all types of people. It really is what American democracy is supposed to be.”

— Wynton Marsalis

Jazz and the Great Migration Playlist

Big Ideas

Renaissance

A movement or period of great activity (as in literature, science, and the arts).

Community

An interacting population of various kinds of people in a common location.

Culture

The way of life, especially the customs and beliefs of a particular group of people.

Exploring the Blues

Saxophonist Camille Thurman guides us through the Blues, and shows us how the Blues is a building block of Jazz!

When Big Bands Were Dance Bands

Guitarist James Chirillo, bassist Ari Roland, and drummer Alvin Atkinson remind you that big bands performed for dancers, and show you how to keep a strong sense of swing in your rhythm section work, no matter how fast or slow the tempo.

Jazz Leave New Orleans

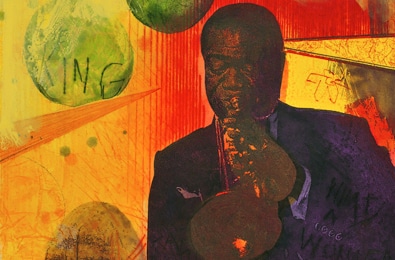

Who was King Oliver, and what was his contribution to the growing popularity of Jazz and the continuing innovations in the art form? Jazz at Lincoln Center’s curator Phil Schaap explains Jazz’s part in the Great Migration, and talks about one of the music’s first stars.